The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of this site. This site does not give financial, investment or medical advice.

(Meduza) – On September 1, the United States dramatically cut the size of its diplomatic staff in Russia, as demanded by the Foreign Ministry. For ordinary Russians, the direct consequence of the reduction has been a de facto tightening of the U.S. visa regime. People living far from Moscow can no longer get American visas at their nearest consulate, and applicants in the capital are waiting far longer than before. Many Russians now prefer to apply for U.S. visas in neighboring countries, and Meduza has learned that the American embassies just outside Russia are struggling to manage the new influx of eager travelers.

Moscow issued its diplomatic-cutback demands to the United States on July 28, describing the measure as a response to Washington’s decision to expel 35 diplomats from the U.S. in December 2016. The Foreign Ministry said the reductions would establish parity in Russian-American diplomatic presences. In August, American officials announced that they would stop issuing visas at the U.S. consulates in St. Petersburg, Yekaterinburg, and Vladivostok, making the U.S. embassy in Moscow the only place to get an American visa in the country. Even Russians who’d already signed up for their visas at their local consulates were now required to come to the capital to receive them.

As a result, the number of U.S. visas granted to Russians in September 2017 fell sharply. According to statistics from the State Department, the number of U.S. visas granted to Russian citizens at embassies and consulates around the world averaged 15,000 to 20,000 per month, throughout the summer. In September, however, the number dropped to 7,110 (including 5,104 tourist visas).

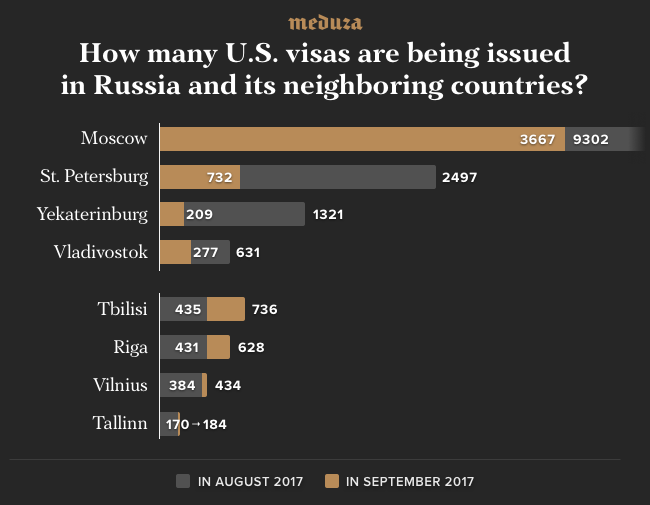

To a large extent, this decline was due to the diminished visa activity of America’s consulates in Russia. For example, the St. Petersburg consulate issued more than 3,000 visas in an average month between March and July 2017. In September, this figure fell to just 732 (this number includes immigrant visas, visas issued to non-Russian citizens, and visas where an interview is not required). The U.S. consulate in Yekaterinburg issued 84 percent fewer visas in September, and in Vladivostok the number of new visas fell by 66 percent.

The number of U.S. visas granted in Moscow between August and September fell by 61 percent: 3,667 visas were issued in September, and 9,302 in August. For comparison, the same embassy issued an average of 13,000 visas a month during the spring.

Maria Olson, the spokesperson for the U.S. embassy in Moscow, told Meduza that the State Department’s September figures include some of the visas that were already in process before August 21, when America imposed new restrictions on the issuance of nonimmigrant visas. The number of U.S. visas issued to Russians in October is expected to be even lower.

At the same time, the number of American visas issued by embassies just outside Russia has spiked. In Vilnius, Lithuania, visas are up 13 percent (and tourist visas are up 28 percent); in Tallinn, Estonia, it’s 8 percent and 77 percent; in Tbilisi, Georgia, it is 77 percent and 160 percent; and so on. These higher numbers of tourist visas issued (especially in cities within the European Union, where citizens don’t need tourist visas to visit the United States) is circumstantial evidence that more foreign citizens are flocking to these embassies with visa applications.

American diplomatic spokespeople in Riga, Tallinn, and Vilnius would not confirm to Meduza that more Russian citizens started applying for U.S. visas at their embassies after September 1, but they admitted that the number of visa applications from foreigners has recently grown “significantly.”

“Russian citizens, like citizens of any other country, have the right to apply for American visas at our embassies and consulates anywhere around the world,” said Chad Twitty, the public affairs officer for the U.S. embassy in Latvia.

A source familiar with the work of American diplomatic missions admitted to Meduza that the number of U.S. visa applications from Russian citizens has spiked in all three Baltic states (Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia). Meduza has also learned that some U.S. embassies have had to organize separate waiting lines for Russians and locals. In Riga, for example, the processing time for a visa application submitted by a Latvian citizen averages two days, but for Russian citizens it can take up to several weeks (Meduza’s source says he submitted his visa application in Riga in mid-October, and the embassy offered him a visa interview in mid-December).

American diplomatic staff would not confirm these reports, and embassy spokespeople in Riga and Tallinn told Meduza simply that any visa applicants should “submit their documents as early as possible.”

The visa situation in Moscow, meanwhile, is becoming increasingly hopeless for Russians wanting to visit the United States. According to the State Department’s official travel website, the projected wait time for interviews at its Moscow embassy is currently 85 days after the submission of a visa application, though officials provided the same estimate in August. The real waiting period in Russia is actually many months, and some visa applicants say they’ve been told plainly that there are currently no open dates at all for an interview.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of this site. This site does not give financial, investment or medical advice.